NOT many may be aware of the fact that R G Kar Medical College and Hospital is named after Dr Radha Gobinda Kar, the Renaissance man of medical science in British-ruled Bengal.

Kar dedicated his life towards making the healthcare system accessible to the people of Bengal. Today, doctors, staff, students, the entire city, women — not just in Kolkata but across the country — have united to push for what Kar envisaged. Drawing strength from their grief, trauma and shock over the rape and murder of a post-graduate trainee doctor, they have put their foot down — to stand up for their rights.

This is remarkable. In these divided times, their cause finds a united echo across the country. Left, right or centre, poor or rich, rural or urban, everyone is invested in the future being a place where their children are safe and can follow their dreams.

Parallels have been drawn between the Kolkata rape-murder and the Delhi rape in 2012. That was in an empty bus being steered along the Capital’s streets by a group of predatory men. This was in a hospital in the heart of the city.

There are several deeply disquieting aspects to the incident, symptomatic of West Bengal’s steady “transformation” towards deterioration. I know this as someone who has spent decades in public life here; I have been a witness to this, I have spoken against this, I have resisted this.

So when Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee writes to Prime Minister Narendra Modi asking for a tougher law against rape, I wish to remind her that law and order is on the Concurrent List, that the police are under her watch, the hospital is under her government.

When her nephew and party potentate Abhishek Banerjee says “hooliganism and vandalism” have “exceeded all acceptable limits” and adds, that the rapists “who don’t deserve to live in society, should be dealt with either through encounter or by hanging”, I wish to tell him that these words ring hollow.

This call for vigilante justice doesn’t betray sincerity, it is bluster meant to conceal a larger rot in the system, a rot that his party has helped nurture.

Violence, including crime against women, has become grist to the state’s political mill.

Just look at the string of incidents involving alleged sexual assault where ruling-party supporters are complicit and accused. Over the years, almost every aspect of life in West Bengal has come to be touched by the corrupt syndicates led by the ruling elite. These operate at all levels – from a city neighbourhood to a remote village – with ill-gotten wealth.

Not just that. Every institution is hijacked by the ruling establishment so that there is a toxic nexus between rulers, lawmakers, criminals and lawkeepers.

When the line between the party office and the thana gets blurred, the social compact between the citizen and the state breaks down. The Chief Minister setting out on a padyatra fails to instill a sense of security or hope. Instead, it becomes a symbol of state abdication.

As a public representative in the Lok Sabha from West Bengal for five consecutive terms before the 18th Lok Sabha election, and parent to a daughter, what pains me at a personal level, is that this has happened in a city with an illustrious tradition of respect for women.

Where women have claimed the public space long before their sisters did in other states. Where almost a century ago, revolutionary leader Matangini Hazra stood up to imperialist rulers and paid with her life.

The architects of the Renaissance, social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy, writer Rabindranath Tagore, physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, poet Kazi Nazrul Islam and educationist Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, all brought about a deep awakening across the country.

Indeed, the Bengal Province was the nerve centre of the cultural Renaissance in India in the run-up to Independence.

The epicentre of the current protests is a hospital that’s part of the same history.

Kar, having graduated with honours in medical science from the University of Edinburgh, had the option of practising medicine in the UK. But he chose to return to his motherland, Bengal, to dedicate his life to serving the poor.

It was his relentless campaign to raise funds from the rich and his dogged perseverance in treating the poor in north Kolkata that made the hospital a boon for those in need.

Established in 1886 as the Calcutta School of Medicine, it was in 1948, at the initiative of then chief minister of West Bengal, Bidhan Chandra Roy, that the hospital acquired its present name.

That’s why I hold hope. The RG Kar rape-murder doesn’t need to be just a statistic.

It has triggered a social and public movement calling for change, one that demands safer public spaces, better governance in the state and a more peaceful social order.

In the picket lines, we have seen everyone: Girls, women, boys, men, all speaking up spontaneously at the risk of being blacklisted or arrested. Consequently, the nervousness of the state’s ruling elite is becoming more evident.

I am sure that these protests are not in vain. As a politician, I know that change is never easy but I also know that when people decide to speak up, to stand up, to not be afraid of any threat or intimidation, change is inevitable. For, this is Bengal’s history, its present, and it will remain its future.

ends

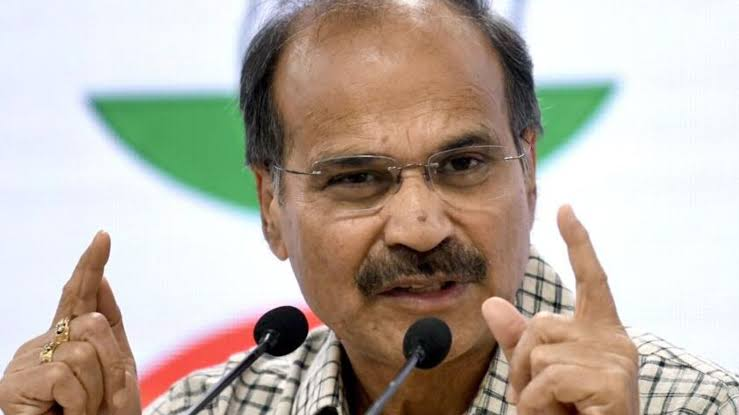

(The writer - a senior Congress leader was Lok Sabha MP for five consecutive terms, former Minister of State for Railways. He was chairperson of the Public Accounts Committee of Parliament in the 17th Lok Sabha and also Congress floor leader. He also served as president of West Bengal Pradesh Congress Committee.) Views are personal

No comments:

Post a Comment